The Oklahoma Girl Scout Murders (1977)

- Strange Case Files

- Jan 8

- 4 min read

Three girls were killed on their first night at camp. A warning note was dismissed. The only man ever tried was found not guilty. The case remains officially unsolved.

A Quiet Camp in Eastern Oklahoma

In June 1977, Girl Scouts arrived at Camp Scott in Mayes County, Oklahoma, near Locust Grove. The camp sat in dense woods, with cabins, trails, and tent units spread across a large area.

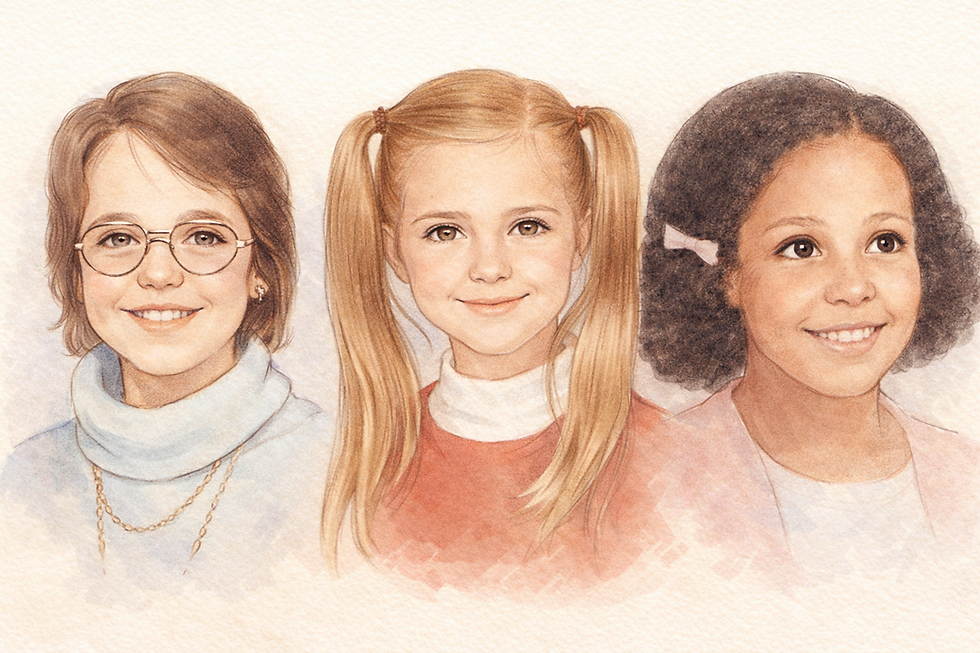

Three campers from the Tulsa area were assigned to the Kiowa unit: Lori Lee Farmer (8), Michele Heather Guse (9), and Doris Denise Milner (10). The girls shared tent 7, positioned farther from the counselors’ area and partly obscured by nearby camp facilities, including the shower building.

The Note That Was Thrown Away

Less than two months before the murders, during an on-site training session for camp staff, a counselor reported that her belongings had been disturbed and food had been taken. Inside an empty doughnut box was a handwritten note warning that someone was “on a mission to kill three girls in tent one.”

The note was treated as a prank and discarded.

It would later become one of the most haunting “what if” details in the entire case, not because it matched the victims’ tent number, but because it suggested someone had entered the camp area before and wanted to be remembered for it.

The First Night

The girls’ first night at camp was unsettled by severe weather. Reports from the time describe storms moving through the area overnight.

In the early morning hours of June 13, 1977, the three girls were taken from their tent.

Around 6:00 a.m., a counselor walking toward the showers noticed what appeared to be a sleeping bag with a girl inside in a wooded area near the tent sites. Camp staff soon realized the three girls from tent 7 were missing.

A search led to a grim discovery: the girls were found on a trail leading toward the showers, roughly 150 yards from their tent. Authorities later concluded the girls had been killed by strangulation and blunt force injuries. Investigators also determined the girls had been sexually assaulted.

Camp Scott was immediately evacuated.

A Fast Investigation, Then Confusion

The case drew intense attention and pressure to identify a suspect quickly. The crime scene had been exposed to storm conditions, which likely complicated the collection of physical evidence. As the investigation unfolded, there were also highly publicized missteps and contradictions.

One example often cited in later reporting involves fingerprints. At one point, authorities publicly suggested strong fingerprint evidence existed. Later accounts clarified that the usable print evidence did not deliver the identification many believed it would.

Another detail from contemporary reporting described how investigators found photographs in the woods and attempted to connect them to a suspect. That thread became part of a broader debate about how evidence was handled and interpreted during a high-pressure manhunt.

Gene Leroy Hart Becomes the Central Suspect

Investigators focused on Gene Leroy Hart, a local man who had escaped custody in 1973 and had a history of serious sexual violence and burglary. He knew the area and had lived nearby.

Hart was arrested within a year of the murders and charged. The case went to trial in March 1979.

Public opinion was sharply divided. Some believed he was the obvious suspect. Others believed the case against him relied too heavily on circumstance and interpretation.

The jury returned a unanimous not guilty verdict. No one was convicted for the murders.

Hart remained incarcerated because of earlier convictions and died in prison in June 1979 after suffering a heart attack.

The Lawsuit and the Question of Preventability

In the years after the murders, the Girl Scout council faced a civil lawsuit from families alleging negligence. The case centered on questions that still echo today: the earlier note, camp layout, supervision, and security decisions.

A jury ultimately found in favor of the council.

Even so, the case helped accelerate changes in how many camps approached safety planning, staffing patterns, and risk awareness.

DNA Testing and What It Actually Indicates

Because this case is often summarized online in oversimplified ways, this part matters.

Public reporting and later summaries describe DNA testing in 1989 as inconclusive, meaning it did not narrow the suspect pool enough to be definitive.

Decades later, additional testing was reported to strongly suggest Hart’s involvement, according to statements attributed to local authorities, but the case remains officially unsolved, and no conviction exists to resolve the question in court.

The key point is that DNA discussions around this case are often presented as final proof one way or the other. The available public record does not support absolute certainty, and the legal outcome remains unchanged.

What Still Has No Answer

Nearly fifty years later, several questions remain central:

Who wrote the threatening note. It referenced tent one, not tent 7, but it indicated someone had violated the camp’s boundaries earlier.

Who had the access and confidence to move through the Kiowa unit at night. The camp’s layout and isolation made concealment easier, but the exact sequence of events is still not fully established publicly.

Whether the original investigation preserved and interpreted evidence in a way that can withstand modern scrutiny. Errors and reversals in early public statements have left lasting doubt, even among people who believe the suspect was identified.

Why the Case Endures: Oklahoma Girl Scout Murders

The Oklahoma Girl Scout murders remain one of the most disturbing unsolved cases in American camp history because they combine three things that rarely coexist cleanly.

A warning sign that was ignored. A trial that ended without a conviction. Later forensic developments that fueled new certainty for some, but not legal closure for all

For the families, the unresolved truth is the same.

Three girls never came home, and the case has never been truly finished.

Comments